- Home

- Natalie Babbitt

Tuck Everlasting

Tuck Everlasting Read online

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Epilogue

Go Fish: Questions for the Author

Prologue

The first week of August hangs at the very top of summer, the top of the live-long year, like the highest seat of a Ferris wheel when it pauses in its turning. The weeks that come before are only a climb from balmy spring, and those that follow a drop to the chill of autumn, but the first week of August is motionless, and hot. It is curiously silent, too, with blank white dawns and glaring noons, and sunsets smeared with too much color. Often at night there is lightning, but it quivers all alone. There is no thunder, no relieving rain. These are strange and breathless days, the dog days, when people are led to do things they are sure to be sorry for after.

One day at that time, not so very long ago, three things happened and at first there appeared to be no connection between them.

At dawn, Mae Tuck set out on her horse for the wood at the edge of the village of Treegap. She was going there, as she did once every ten years, to meet her two sons, Miles and Jesse.

At noontime, Winnie Foster, whose family owned the Treegap wood, lost her patience at last and decided to think about running away.

And at sunset a stranger appeared at the Fosters’ gate. He was looking for someone, but he didn’t say who.

No connection, you would agree. But things can come together in strange ways. The wood was at the center, the hub of the wheel. All wheels must have a hub. A Ferris wheel has one, as the sun is the hub of the wheeling calendar. Fixed points they are, and best left undisturbed, for without them, nothing holds together. But sometimes people find this out too late.

1

The road that led to Treegap had been trod out long before by a herd of cows who were, to say the least, relaxed. It wandered along in curves and easy angles, swayed off and up in a pleasant tangent to the top of a small hill, ambled down again between fringes of bee-hung clover, and then cut sidewise across a meadow. Here its edges blurred. It widened and seemed to pause, suggesting tranquil bovine picnics: slow chewing and thoughtful contemplation of the infinite. And then it went on again and came at last to the wood. But on reaching the shadows of the first trees, it veered sharply, swung out in a wide arc as if, for the first time, it had reason to think where it was going, and passed around.

On the other side of the wood, the sense of easiness dissolved. The road no longer belonged to the cows. It became, instead, and rather abruptly, the property of people. And all at once the sun was uncomfortably hot, the dust oppressive, and the meager grass along its edges somewhat ragged and forlorn. On the left stood the first house, a square and solid cottage with a touch-me-not appearance, surrounded by grass cut painfully to the quick and enclosed by a capable iron fence some four feet high which clearly said, “Move on—we don’t want you here.” So the road went humbly by and made its way, past cottages more and more frequent but less and less forbidding, into the village. But the village doesn’t matter, except for the jailhouse and the gallows. The first house only is important; the first house, the road, and the wood.

There was something strange about the wood. If the look of the first house suggested that you’d better pass it by, so did the look of the wood, but for quite a different reason. The house was so proud of itself that you wanted to make a lot of noise as you passed, and maybe even throw a rock or two. But the wood had a sleeping, otherworld appearance that made you want to speak in whispers. This, at least, is what the cows must have thought: “Let it keep its peace; we won’t disturb it.”

Whether the people felt that way about the wood or not is difficult to say. There were some, perhaps, who did. But for the most part the people followed the road around the wood because that was the way it led. There was no road through the wood. And anyway, for the people, there was another reason to leave the wood to itself: it belonged to the Fosters, the owners of the touch-me-not cottage, and was therefore private property in spite of the fact that it lay outside the fence and was perfectly accessible.

The ownership of land is an odd thing when you come to think of it. How deep, after all, can it go? If a person owns a piece of land, does he own it all the way down, in ever narrowing dimensions, till it meets all other pieces at the center of the earth? Or does ownership consist only of a thin crust under which the friendly worms have never heard of trespassing?

In any case, the wood, being on top—except, of course, for its roots—was owned bud and bough by the Fosters in the touch-me-not cottage, and if they never went there, if they never wandered in among the trees, well, that was their affair. Winnie, the only child of the house, never went there, though she sometimes stood inside the fence, carelessly banging a stick against the iron bars, and looked at it. But she had never been curious about it. Nothing ever seems interesting when it belongs to you—only when it doesn’t.

And what is interesting, anyway, about a slim few acres of trees? There will be a dimness shot through with bars of sunlight, a great many squirrels and birds, a deep, damp mattress of leaves on the ground, and all the other things just as familiar if not so pleasant—things like spiders, thorns, and grubs.

In the end, however, it was the cows who were responsible for the wood’s isolation, and the cows, through some wisdom they were not wise enough to know that they possessed, were very wise indeed. If they had made their road through the wood instead of around it, then the people would have followed the road. The people would have noticed the giant ash tree at the center of the wood, and then, in time, they’d have noticed the little spring bubbling up among its roots in spite of the pebbles piled there to conceal it. And that would have been a disaster so immense that this weary old earth, owned or not to its fiery core, would have trembled on its axis like a beetle on a pin.

2

And so, at dawn, that day in the first week of August, Mae Tuck woke up and lay for a while beaming at the cobwebs on the ceiling. At last she said aloud, “The boys’ll be home tomorrow!”

Mae’s husband, on his back beside her, did not stir. He was still asleep, and the melancholy creases that folded his daytime face were smoothed and slack. He snored gently, and for a moment the corners of his mouth turned upward in a smile. Tuck almost never smiled except in sleep.

Mae sat up in bed and looked at him tolerantly. “The boys’ll be home tomorrow,” she said again, a little more loudly.

Tuck twitched and the smile vanished. He opened his eyes. “Why’d you have to wake me up?” he sighed. “I was having that dream again, the good one where we’re all in heaven and never heard of Treegap.”

Mae sat there frowning, a great potato of a woman with a round, sensible face and calm brown eyes. “It’s no use having that dream,” she said. “Nothing’s going to change.”

“You tell me that every day,” said Tuck, turning away from her onto his side. “Anyways, I can’t help what I dream.”

“Maybe not,” said Mae. “But, all the same, you should’ve got used to things by now.”

Tuck groaned. “I’m going back to sleep,” he said.

“Not me,” said Mae. “

I’m going to take the horse and go down to the wood to meet them.”

“Meet who?”

“The boys, Tuck! Our sons. I’m going to ride down to meet them.”

“Better not do that,” said Tuck.

“I know,” said Mae, “but I just can’t wait to see them. Anyways, it’s ten years since I went to Treegap. No one’ll remember me. I’ll ride in at sunset, just to the wood. I won’t go into the village. But, even if someone did see me, they won’t remember. They never did before, now, did they?”

“Suit yourself, then,” said Tuck into his pillow. “I’m going back to sleep.”

Mae Tuck climbed out of bed and began to dress: three petticoats, a rusty brown skirt with one enormous pocket, an old cotton jacket, and a knitted shawl which she pinned across her bosom with a tarnished metal brooch. The sounds of her dressing were so familiar to Tuck that he could say, without opening his eyes, “You don’t need that shawl in the middle of the summer.”

Mae ignored this observation. Instead, she said, “Will you be all right? We won’t get back till late tomorrow.”

Tuck rolled over and made a rueful face at her. “What in the world could possibly happen to me?”

“That’s so,” said Mae. “I keep forgetting.”

“I don’t,” said Tuck. “Have a nice time.” And in a moment he was asleep again.

Mae sat on the edge of the bed and pulled on a pair of short leather boots so thin and soft with age it was a wonder they held together. Then she stood and took from the washstand beside the bed a little square-shaped object, a music box painted with roses and lilies of the valley. It was the one pretty thing she owned and she never went anywhere without it. Her fingers strayed to the winding key on its bottom, but glancing at the sleeping Tuck, she shook her head, gave the little box a pat, and dropped it into her pocket. Then, last of all, she pulled down over her ears a blue straw hat with a drooping, exhausted brim.

But, before she put on the hat, she brushed her gray-brown hair and wound it into a bun at the back of her neck. She did this quickly and skillfully without a single glance in the mirror. Mae Tuck didn’t need a mirror, though she had one propped up on the washstand. She knew very well what she would see in it; her reflection had long since ceased to interest her. For Mae Tuck, and her husband, and Miles and Jesse, too, had all looked exactly the same for eighty-seven years.

3

At noon of that same day in the first week of August, Winnie Foster sat on the bristly grass just inside the fence and said to the large toad who was squatting a few yards away across the road, “I will, though. You’ll see. Maybe even first thing tomorrow, while everyone’s still asleep.”

It was hard to know whether the toad was listening or not. Certainly, Winnie had given it good reason to ignore her. She had come out to the fence, very cross, very near the boiling point on a day that was itself near to boiling, and had noticed the toad at once. It was the only living thing in sight except for a stationary cloud of hysterical gnats suspended in the heat above the road. Winnie had found some pebbles at the base of the fence and, for lack of any other way to show how she felt, had flung one at the toad. It missed altogether, as she’d fully intended it should, but she made a game of it anyway, tossing pebbles at such an angle that they passed through the gnat cloud on their way to the toad. The gnats were too frantic to notice these intrusions, however, and since every pebble missed its final mark, the toad continued to squat and grimace without so much as a twitch. Possibly it felt resentful. Or perhaps it was only asleep. In either case, it gave her not a glance when at last she ran out of pebbles and sat down to tell it her troubles.

“Look here, toad,” she said, thrusting her arms through the bars of the fence and plucking at the weeds on the other side. “I don’t think I can stand it much longer.”

At this moment a window at the front of the cottage was flung open and a thin voice—her grandmother’s—piped, “Winifred! Don’t sit on that dirty grass. You’ll stain your boots and stockings.”

And another, firmer voice—her mother’s—added, “Come in now, Winnie. Right away. You’ll get heat stroke out there on a day like this. And your lunch is ready.”

“See?” said Winnie to the toad. “That’s just what I mean. It’s like that every minute. If I had a sister or a brother, there’d be someone else for them to watch. But, as it is, there’s only me. I’m tired of being looked at all the time. I want to be by myself for a change.” She leaned her forehead against the bars and after a short silence went on in a thoughtful tone. “I’m not exactly sure what I’d do, you know, but something interesting—something that’s all mine. Something that would make some kind of difference in the world. It’d be nice to have a new name, to start with, one that’s not all worn out from being called so much. And I might even decide to have a pet. Maybe a big old toad, like you, that I could keep in a nice cage with lots of grass, and…”

At this the toad stirred and blinked. It gave a heave of muscles and plopped its heavy mudball of a body a few inches farther away from her.

“I suppose you’re right,” said Winnie. “Then you’d be just the way I am, now. Why should you have to be cooped up in a cage, too? It’d be better if I could be like you, out in the open and making up my own mind. Do you know they’ve hardly ever let me out of this yard all by myself? I’ll never be able to do anything important if I stay in here like this. I expect I’d better run away.” She paused and peered anxiously at the toad to see how it would receive this staggering idea, but it showed no signs of interest. “You think I wouldn’t dare, don’t you?” she said accusingly. “I will, though. You’ll see. Maybe even first thing in the morning, while everyone’s still asleep.”

“Winnie!” came the firm voice from the window.

“All right! I’m coming!” she cried, exasperated, and then added quickly, “I mean, I’ll be right there, Mama.” She stood up, brushing at her legs where bits of itchy grass clung to her stockings.

The toad, as if it saw that their interview was over, stirred again, bunched up, and bounced itself clumsily off toward the wood. Winnie watched it go. “Hop away, toad,” she called after it. “You’ll see. Just wait till morning.”

4

At sunset of that same long day, a stranger came strolling up the road from the village and paused at the Fosters’ gate. Winnie was once again in the yard, this time intent on catching fireflies, and at first she didn’t notice him. But, after a few moments of watching her, he called out, “Good evening!”

He was remarkably tall and narrow, this stranger standing there. His long chin faded off into a thin, apologetic beard, but his suit was a jaunty yellow that seemed to glow a little in the fading light. A black hat dangled from one hand, and as Winnie came toward him, he passed the other through his dry, gray hair, settling it smoothly. “Well, now,” he said in a light voice. “Out for fireflies, are you?”

“Yes,” said Winnie.

“A lovely thing to do on a summer evening,” said the man richly. “A lovely entertainment. I used to do it myself when I was your age. But of course that was a long, long time ago.” He laughed, gesturing in self-deprecation with long, thin fingers. His tall body moved continuously; a foot tapped, a shoulder twitched. And it moved in angles, rather jerkily. But at the same time he had a kind of grace, like a well-handled marionette. Indeed, he seemed almost to hang suspended there in the twilight. But Winnie, though she was half charmed, was suddenly reminded of the stiff black ribbons they had hung on the door of the cottage for her grandfather’s funeral. She frowned and looked at the man more closely. But his smile seemed perfectly all right, quite agreeable and friendly.

“Is this your house?” asked the man, folding his arms now and leaning against the gate.

“Yes,” said Winnie. “Do you want to see my father?”

“Perhaps. In a bit,” said the man. “But I’d like to talk to you first. Have you and your family lived here long?”

“Oh, yes,” said Winnie. �

��We’ve lived here forever.”

“Forever,” the man echoed thoughtfully.

It was not a question, but Winnie decided to explain anyway. “Well, not forever, of course, but as long as there’ve been any people here. My grandmother was born here. She says this was all trees once, just one big forest everywhere around, but it’s mostly all cut down now. Except for the wood.”

“I see,” said the man, pulling at his beard. “So of course you know everyone, and everything that goes on.”

“Well, not especially,” said Winnie. “At least, I don’t. Why?”

The man lifted his eyebrows. “Oh,” he said, “I’m looking for someone. A family.”

“I don’t know anybody much,” said Winnie, with a shrug. “But my father might. You could ask him.”

“I believe I shall,” said the man. “I do believe I shall.”

At this moment the cottage door opened, and in the lamp glow that spilled across the grass, Winnie’s grandmother appeared. “Winifred? Who are you talking to out there?”

“It’s a man, Granny,” she called back. “He says he’s looking for someone.”

“What’s that?” said the old woman. She picked up her skirts and came down the path to the gate. “What did you say he wants?”

The man on the other side of the fence bowed slightly. “Good evening, madam,” he said. “How delightful to see you looking so fit.”

“And why shouldn’t I be fit?” she retorted, peering at him through the fading light. His yellow suit seemed to surprise her, and she squinted suspiciously. “We haven’t met, that I can recall. Who are you? Who are you looking for?”

-->

The Eyes of the Amaryllis

The Eyes of the Amaryllis Herbert Rowbarge

Herbert Rowbarge The Search for Delicious

The Search for Delicious Kneeknock Rise

Kneeknock Rise Goody Hall

Goody Hall Tuck Everlasting

Tuck Everlasting The Devil's Storybook

The Devil's Storybook The Moon Over High Street

The Moon Over High Street Phoebe's Revolt

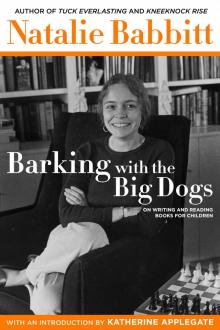

Phoebe's Revolt Barking with the Big Dogs

Barking with the Big Dogs The Devil's Storybooks

The Devil's Storybooks